Turkish mining hopes to strike gold

From Portugal to China, Eurasia is rich in minerals that are vital to modern life and prosperity. Straddling the two continents is Turkey, where industrial raw materials, rare earth minerals and precious metals can be found in abundance deep beneath the ground. The country sits on prime real estate – notably, an underexplored area of the Tethyan Metallogenic Belt that stretches from the Alps to beyond the Himalayas.

Political turbulence and an economic decline have plunged Turkey into a

state of uncertainty

Over the past two decades, gold mining has become an increasingly significant industry for Turkey. Boosted by the privatisation of the sector, the government’s infrastructure push and the fact that operating costs in Turkey are among the lowest in the world, gold mining has thrived. In the past 19 years, 15 gold mines have sprung up and production has soared, making the country Europe’s leading producer of the precious metal. But while Turkey’s gold mining boom is still in its infancy, concerns over political stability and tough regulatory processes have dampened growth, raising questions about the industry’s long-term future.

Gold rush

However, in 2012, the government introduced a raft of measures aimed at making the country more appealing to foreign investors, including a broad range of incentives for the mining industry. According to Invest in Turkey, the government provides a minimum of TRY 50m ($8.6m) to the mining sector under its large-scale investment scheme, with incentives such as a reduced tax rate and exemptions from customs duties and VAT. These policies, along with the expanding road network and the adoption of 4G across the country, have helped attract foreign investors to Turkey’s budding mining industry. “We have the government on our side,”

Kerim Sener, managing director of gold exploration and development firm

And there is the potential for even more growth in Turkey’s mining industry. In 2018, Ali Emiroğlu, President of the Turkish Miners Association, told

Cutting red tape

More recently, though, the mining boom has faltered, with political instability and permitting issues causing investment – as well as the expansion of new gold mines – to slow. By 2017, production had dipped to around 22.5 tonnes per year and total foreign direct investment (FDI) had slumped to around $11bn, down from nearly $18bn in 2015, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s (UNCTAD’s)

Fatih Kaya, a senior consultant at Invist FC, which advises investors in Turkey, told

World Finance

that bureaucracy and red tape have been holding the mining sector back. For instance, Kaya said miners must obtain 21 permits and authorisations from various ministries and agencies before they begin work on a mine – a process that typically takes two and a half years. Kaya believes this must be simplified in order to encourage growth: “The whole process needs to be designed very transparently to assure foreign direct investors that [they are] treated equally [to] other parties in order not to create disproportionate behaviours and unfair treatment.” The process, however, has not discouraged Sener, who argued that licensing has its hurdles anywhere in the world: “Permitting in Turkey is hardly different to other parts of the western world, although there are complications and delays.”

But difficult licensing processes are not the only factor potentially denting Turkey’s global image in the eyes of investors: the country’s poor record for workplace accidents is another area of contention. For the mining sector, this was exemplified by the Soma mine disaster of 2014. The incident, in which 301 coal miners died following a fire, was the worst mining accident in Turkey’s history. Although health and safety measures have improved since the catastrophe, workplace accidents are common throughout the country. In 2017, the Workers’ Health and Work Safety Assembly revealed that 2,006 workers had been killed in occupational accidents – up by 36 from the previous year.

While the 93 deaths attributed to the mining sector were far below those recorded in the construction, agriculture or transportation sectors, the figure has failed to improve, on average, since the Soma incident. In comparison, Australia’s larger and more developed mining sector recorded three mining-related deaths in 2018, according to preliminary data from the governmental body Safe Work Australia.

“The [Turkish] Government is well aware of the problem and the [mining department] is logging incidents carefully,” Sener said. “[However,] the country has the ability to do so much better… What’s been happening is a push for growth almost at any cost.”

A precarious state

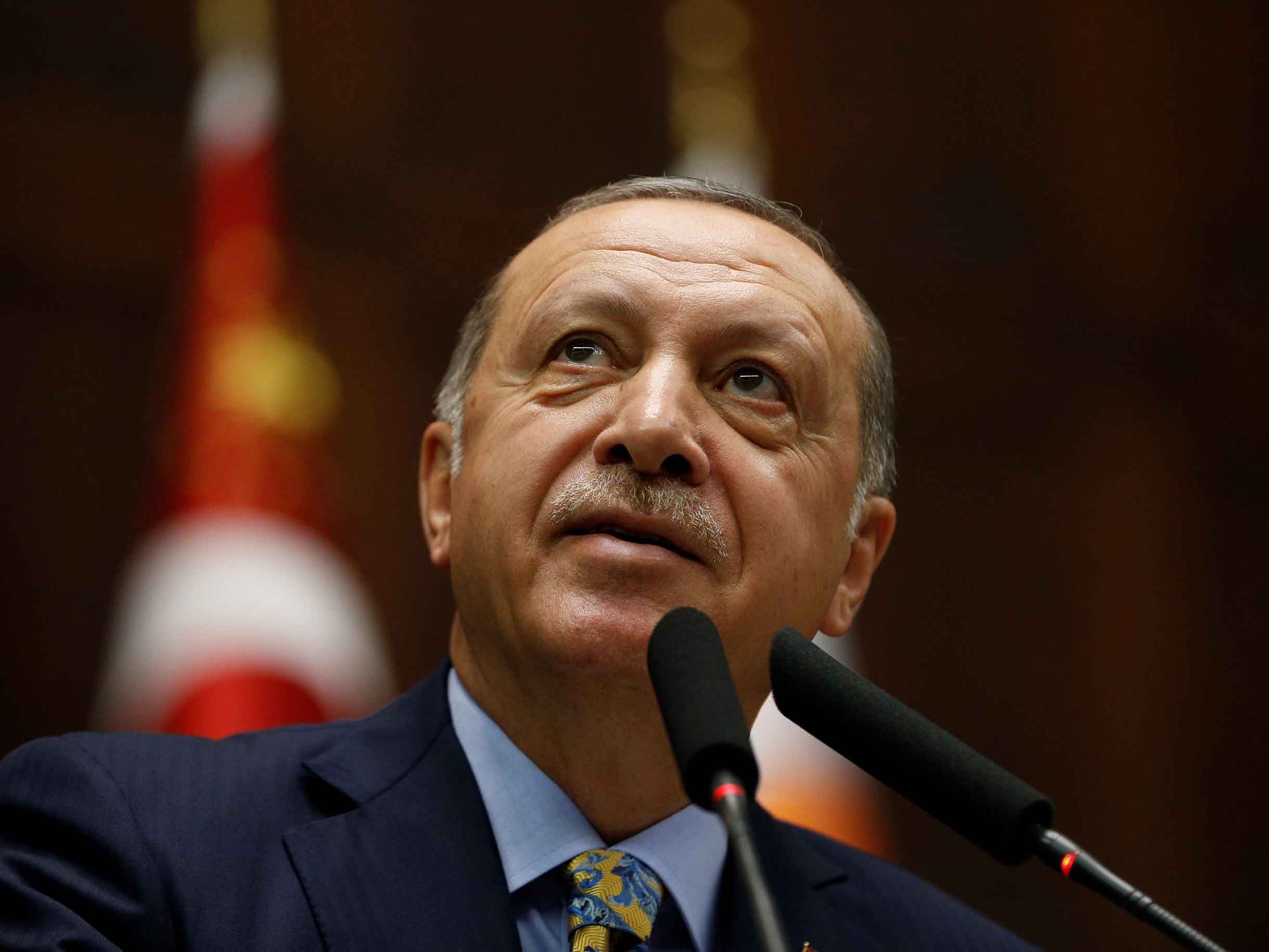

As the world’s fourth-largest consumer of gold, Turkey has always had a strong relationship with the costly commodity. And yet, the country’s mining success is a relatively recent phenomenon – in fact, Turkey’s first gold mine only began production in 2001. The rapid development of the mining sector was kick-started by the privatisation of the industry in the early 2000s: this came alongside a broader infrastructure push by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party), which came to power in 2002 under the leadership of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Since then, the government’s stance on foreign miners has transformed. As geologist

According to the Turkish Gold Miners Association, gold production in Turkey peaked at 33.5 tonnes in 2013 (

see Fig 1

), as an influx of foreign investors from mining strongholds such as Canada and Australia arrived. The total value of Turkey’s mining exports hit an all-time high of $5.04bn the same year.

While Turkey has recorded strong overall growth since 2000, political turbulence and economic decline have plunged the country into a state of uncertainty. The relative stability that followed the AK Party’s ascension to power in 2002 fell apart with a failed coup d’état in July 2016, when a coordinated military operation was launched to overthrow Erdoğan. Although the government quickly defeated the attempted coup, more than 200 people died and a further 2,000 were injured. According to the GBR, the day “fundamentally altered the course of the Turkish Republic in ways [that] are still reverberating”.